3 Thoughts On Physicians & Career Modification

Non-clinical and non-traditional medical careers are a common theme on Freelance MD.

Non-clinical and non-traditional medical careers are a common theme on Freelance MD.

If you peruse the posts on Freelance MD you'll find articles on a variety of topics—writing and publishing, real estate investing, concierge medicine, medical device development, business skills, leadership, journalism, and many more.

The common theme of all these posts is the idea of career change, or as I like to call it, career modification. It's the idea that as a physician, you aren't forced to accept the status quo; you have options, and there are a variety of ways in which you can harness your skills and personality traits.

Having said this, however, I must say that it is very difficult for the typical physician to make any kind of career change. It's been a long time since I've met a physician who wasn't significantly frustrated with their career, but I'd say maybe only one out of fifty, or even one out of a hundred, of these frustrated physicians are actively taking steps to modify their career in some meaningful way. It's a strange phenomenon, but it does seem to be a cultural trait in our profession.

Look, I'm not a professional career counselor. If you want professional guidance, I'd suggest Ashley Wendel, whose entire career is focused on helping physicians transition into more satisfying careers. However, for those of you who can tolerate my amateurish anecdotes, here are my top three reasons why I believe physicians have a difficult time modifying their careers...

(drum roll please)

1. Physicians are Narrowly Trained

A typical physician is overall a very narrowly trained individual.

The majority of us were science majors in college and then spent a minimum of seven years being crammed full of medical minutia. When we finished our medical training, we had a fairly firm grasp of our area of clinical expertise, but not much else. Few physicians have had any significant exposure to personal finance, the legal system, business transactions, popular writing, art, negotiations, investing, or anything of the like. Many of the physicians who I know who do have a special area of expertise outside of medicine sort of fell into it, or were raised in it by their family upbringing, not necessarily because they sought it out.

When you compare a physician to an attorney, for instance, and the diverse professional experience of the typical person in law or business, it's easy to see why attorneys and business-types seem to transition in and out of careers with a lot more ease than physicians. We know the Krebs Cycle; they know contracts, and corporate structure, and business appropriateness. It's not that we physicians are any more or less as professionals than our peers in other professions because of our narrow training, it's simply that what works in our narrowly defined world doesn't necessarily work elsewhere.

Physicians who have decided to launch into business, or anything else for that matter, without sufficient prep time usually find just how lacking in knowledge they really are. Our narrow training puts a premium on our clinical knowledge and skills-- it takes a high investment of time and resources to obtain a medical degree and become a licensed physician-- but it also condemns us to a narrow career path unless we actively seek out further training.

The good news is that with further training, career transition is much easier. Here at Freelance MD we're committed to exposing physicians to training in a multitude of diverse niches. We don't want the "narrow training" issue to be an excuse anymore for any physician considering a career move.

2. Physicians have Difficulty with Ambiguity

This reason takes a little more to explain.

Think about your medical training and your current medical career. How did you get where you are today?

Few careers are more systematized for more years than a career in medicine. Most physicians began thinking about medical school before college and worked towards medical school as a goal from the beginning of their undergrad education.

Take and excel at my core science classes...check. Take MCAT...check. Get letters of recommendation...check. Send in applications and pray...check.

Once in medical school our lives are completely structured to the point of exhaustion. We are routed into our various specialty tracks and move along the medical assembly-line like widgets, getting the final stamp of approval and then shipped to a place of employment where we dig into our clinical careers, join a medical society, buy a house, begin paying off our school loans, and well, not much else, really.

When we finally take a look around-- years into our clinical careers-- we have no professional experience other than medicine from which to draw and no practical experience in how to transition into something that doesn't have a structure or system to it.

Become an entrepreneur?

Where's the fellowship for entrepreneurial medicine?

Develop a medical device?

Isn't there a masters degree in medical device development somewhere?

Write a book?

I'd love to, but I don't have time to go back and get a college degree in English.

Does this seem familiar?

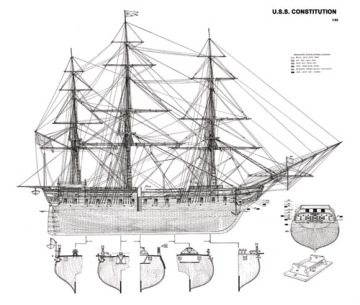

Physicians are so trained in a systematic educational experience of structure and hierarchy that it is very difficult to imagine how an ambiguous career move might work. The idea of setting sail without a predetermined path and system to plug into leaves many physicians completely flummoxed.

Instead of taking a machete and beginning to forge our own path through the career jungle, we wait for someone to build a superhighway that we can follow, complete with rest areas and gourmet coffee shops. Of course, this rarely (read, never) happens so many physicians sit around saturating in the magical thinking that someone will come along with a foolproof plan to save us, and getting more desperate and frustrated when that person doesn't show up.

I could go on and on about this point, but I will use this as an easy transition to my final reason physicians have a difficult time modifying their careers...

3. Physicians are not Risk-Takers

Alright, everybody calm down.

I know you're brave and calm in tense situations. I know you can thread an angiocath, or intubate during a code, or your steady hands can find the pulsating bleeder with the best of them, even when everyone around you is losing control. I know you're good under pressure, but this is not the same as being a person who is comfortable accepting calculated risk.

What I've found in conversations with physicians is that their risk profile is extremely low. Yes, they're frustrated with their careers, but leave their jobs, start a company, move to a different part of the country, invest actual cash in an endeavor? Are you out of your mind? Greg, those things are so risky...

Look folks, here's the facts...

You will never grow, transition to a better career, get from where you are to some better place, move beyond your current boundaries, or do anything of significance without assuming some measure of risk. It's impossible and if you're waiting for that risk-free career move to show up, well my friend, I hope you've got a lot of time on your hands.

Many physicians have a difficult time with this aspect of career modification, even sadly, when the only risk is of the potential damage it might do to their professional standing. I know a number of physicians, for instance, who deep down do not like academic medicine, but who persist in academics because they simply can't bear the thought of what people might say if they left or how it might affect their standing with their peers. They're afraid they'll be dropped from this committee or not invited to speak at that conference. They persist in their academic positions not for the love of teaching or the stimulation of their research; they persist because of the fear that they might lose something in the transition. Their positions have become shackles that confine them, and their peers have become juries whose approval they must have.

When I speak to a physician who is hung up on this aspect of risk, I council them to of course make sure the transition they're considering makes sense-- talk to mentors, read up on the area they're considering jumping into, spend considerable time planning the transition. However, in the end most of these career decisions come down to taking a jump off a cliff, and when I get to this point in the conversation I always discuss with them the risk of the status quo.

You see, career modifications are not a discussion of risk versus no risk. They're a discussion of risk versus risk-- the risk of a career change versus the risk of staying in the same place.

I ask them, "What is the risk of staying in your current position for another year, or two, or three?"

If they're honest, they begin to see that staying in the status quo also carries significant risk, and when this is realized, a potential jump doesn't seem as frightening.

The point is that for most physicians, being able to tolerate risk is not something that comes naturally. We like systems. We like order. We like knowing our next step and we like having safety nets. We work in a culture that demands perfection each and every day and the idea of stepping out without a finalized gameplan is terrifying to most of us. We're creatures of habit with a significant dose of OCD in us-- medical school selects for these traits-- but we have to realize that we'll never begin to grow past where we are if we don't begin stepping out. The idea of growth without risk is ridiculous, and we need to recognize this fallacy and move beyond it. Embracing calculated risk-taking isn't optional, it's mandatory for career modification, and the sooner we accept this the sooner we'll begin moving towards a more fulfilling career. It's that simple.

So there you have it. My three reasons why physicians have a difficult time with career modification.

In future posts I'm going to explain more about what I mean by career modification and some unique perspectives on what is available to physicians in today's modern, fully-wired, world.

Until then, check out Ashley's posts here at Freelance MD or her website. Her advice is excellent for those of you considering a career change, much better than the musings of physician blogger, and almost risk-free.

Almost.

Email This Article tagged:

Email This Article tagged:  Non-Traditional Careers,

Non-Traditional Careers,  Nonclinical Career,

Nonclinical Career,  Physician Career Change |

Physician Career Change |  Dec 22, 12:00 PM

Dec 22, 12:00 PM