Harvard Study: Most Physicians Will Be Sued

New England Journal of Medicine: Most doctors in America will be sued at some point during their career.

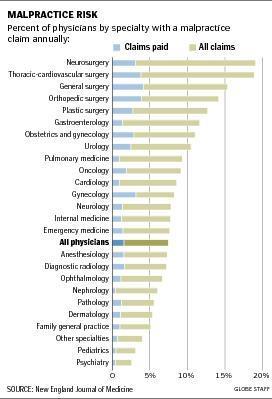

A Harvard study released yesterday in the New England Journal of Medicine has found that physicians who perform high-risk procedures, including neurosurgeons, obstetricians, and thoracic surgeons, face a near certainty of being named in a malpractice case before they reach age 65.

Yet a relatively small number of claims, about 22 percent, result in payments to patients or their families.

Authors of the study, which examined 15 years of data, said it highlights the need for changes in malpractice law so that doctors and patients can resolve disputes before they resort to litigation, which often costs both parties money and heartache.

“Doctors get sued far more frequently than anyone would have thought, and in some specialties, it’s extremely high,’’ said Amitabh Chandra, an economist and professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and an author of the study. “In some sense, the payment is the least important part, because you can insure against it, but you can’t insure against the hassle cost.’’

The study looked at malpractice claims data for nearly 41,000 physicians from 1991 to 2005. The researchers found that 7.4% of physicians had a malpractice claim against them each year and that 1.6% had a claim that led to a payment each year.

Chandra and his coauthor, Dr. Anupam B. Jena of Mass. General, said they hope their study will dispel the fear that many doctors have of big payouts. Their study found just 66 claims that resulted in payments exceeding $1 million. Average claims by specialty ranged from $117,832 in dermatology to $520,923 in pediatrics.

So how can you lessen your chances of being sued by an unhappy patient even further?

Previous studies have shown that patients are less likely to sue when they receive an apology and explanation from their doctor.

Brian Rosman, research director of Health Care for All, said everyone will benefit if patient- doctor communication is divorced from legal proceedings and could actually inprove the quality of care. That would allow doctors and hospitals to deal more directly with the root cause of an error.

One medical society has been working with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, using a $273,782 federal grant, to design a plan for a system that would encourage apologies and compensation, when justified, in Massachusetts. The plan is set to be released this fall.

It seems that nearly universal support exists for a system that encourages doctors to apologize and prevent the escalation of an unwanted outcome into a malpractice lawsuit.

Of course, this wall of scilence goes up on both sides. As soon as an unhappy patient contacts a lawyer they're instructed to have no further contact with the doctor to prevent anything that might mitigate damages or obstruct the lawsuit, like an admission to the doctor that they didn't follow instructions or a 'softening' of their stance as the identify with the physician as a person.

When I was running Surface Medical we ran in to this very problem many times.

Have you been in a lawsuit? Have you ever appologized to a patient?

3 Comments

3 Comments